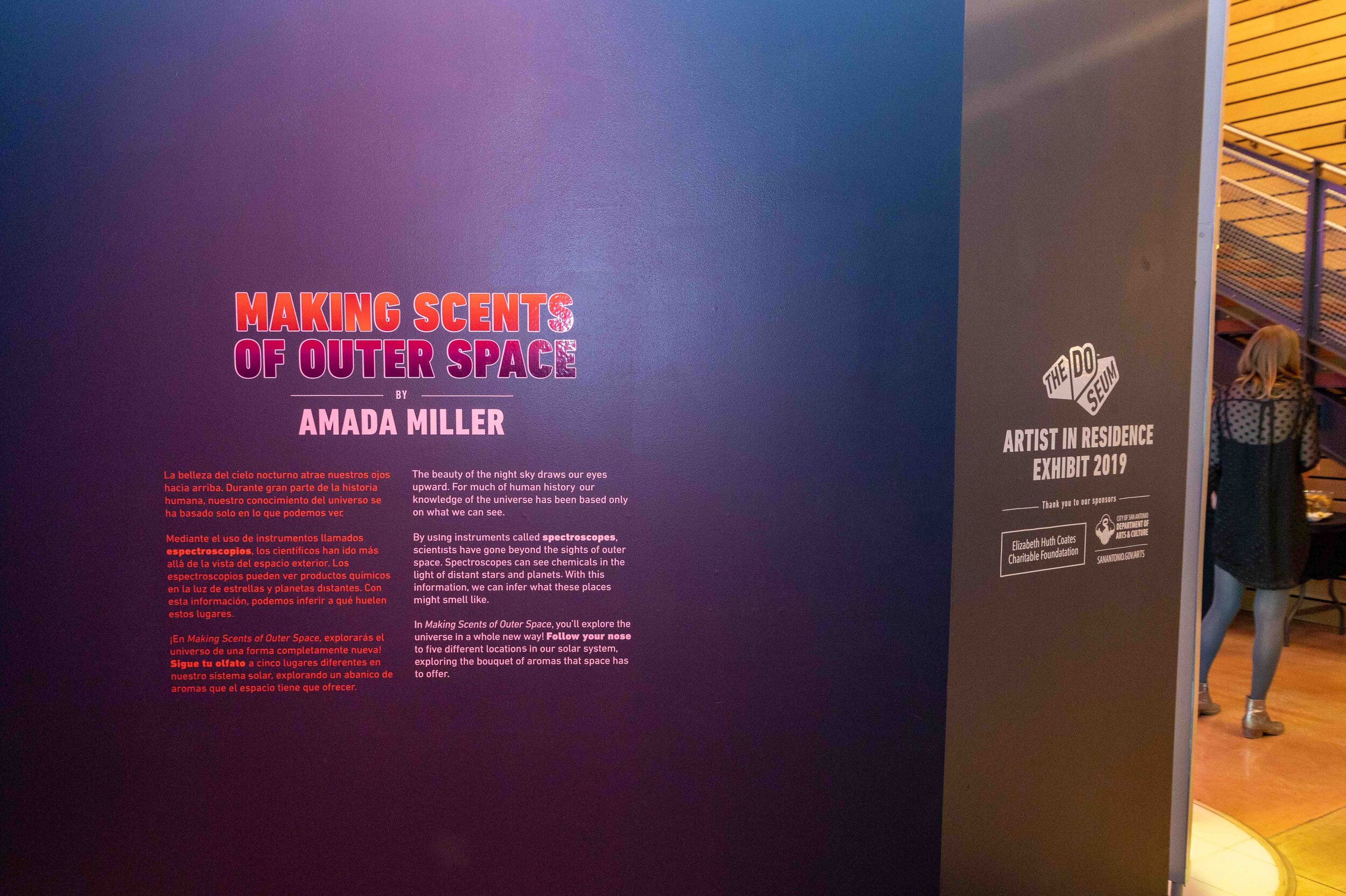

Making Scents of Outer Space

The DoSeum

November 23, 2021 - February 2, 2022

I recently walked into a house that smelled exactly like my grandmother’s. I mean, exactly. Even though I can’t quite describe this scent to you, my mind easily and immediately identified the connection and sent a flood of memories through my mind. I could recall those Texas summers when I sat and watched her work in the kitchen, she cooked all day, every day. The vinyl coating on her retro dining chairs clung to the backs of my sweaty legs and always made me feel slightly uncomfortable. That was a powerful recollection, and the first time I realized how important scent can be in recalling distant memories.

During the summer of 2018, I visited Dr. Ludovic Ferriere, Curator of Meteorites at the Vienna Natural History Museum. I was led through the museums’ meteorite collection, where iron and stone clusters from outer space where propped on pedestals. Dr. Ferriere made a particular point of showing me the Murchison Meteorite, which fell in Australia in 1969. Though this meteorite is old news, it still makes headlines today because of a rare trait; it has a strong and peculiar odor. My mind began racing to consider what other things in outer space smell like. Thankfully, I’m not the only one who’s curious about outer space olfactory sensations. As luck would have it, there’s an entire branch of science dedicated to surveying the chemical compounds of distant planetary bodies, gas clouds, and star clusters. This branch of astrophysics is called Stellar Spectroscopy is the study of starlight spectrums. A measurement device called a spectrometer enables astrophysicists to infer many physical and chemical properties of distant locations and classify them into a logical sequence. We can use this data to infer what other worlds might smell like.

Upon entering Making Sense of Outer Space, visitors encounter five dome structures, each representing a place in space. Earth, The Moon, an exploding star, Sagittarius B2, and a comet. Working with stellar spectrum research, I was able to concoct scent that related to these five places in space, turning them into scratch-and-sniff sculptures that were located inside of each dome and activated by DoSeum visitors.

The first dome on our voyage through the stars is Earth, the pale blue dot we call home. In the Earth dome, visitors can learn about the science behind stellar spectroscopy while considering familiar scents. I chose to represent Earth with the smell of wet dirt.

The Moon dome is unique because humans have actually smelled the moon. From 1969 to 1972, humankind not only set foot onto the lunar surface, but astronauts also collected samples of moon dirt and rocks. Moon dirt is incredibly clingy, sticking to boots and gloves of the moonwalking astronauts. No matter how hard they tried to clean their suits before re-entering their lander, moon dirt made its way inside the cabin. Once their helmets were off, the astronauts could feel, smell and even taste the moon. Apollo 17 astronaut Jack Schmitt told NASA that all the moonwalkers agreed, when they took their helmets off, moon dirt smelled of firecrackers. Curiously, moon samples have no scent on Earth.

The next stop on our journey is an exploding star, which produces smelly compounds called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These tiny molecules seem to be all over the universe, floating around forever, appearing in comets, meteors and space dust. When astronauts are outside of the International Space Station, space-borne compounds adhere to their suits and hitch a ride back into the airlock. Astronauts have reported smelling burned or fried steak after a spacewalk, evoking memories of a barbecue cookout.

Perhaps the most popular dome, and one of my all-time favorite space-scent, is Sagittarius B2, a colossal cloud of dust located at the center of the Milky Way Galaxy. It contains a large amount of ethyl formate, the chemical responsible for giving raspberries their flavor. The unique scent of Sagittarius B2 was discovered by astronomers who have been analyzing the cloud in the hope of finding amino acids—known as the building blocks of life.

Our journey ends with a comet, a frozen ball of gaseous ice that orbits our Sun. In 2014, The European Space Agency’s Rosetta Mission rendezvoused with Comet 67P C/G. Rosetta’s spectrometers picked up the presence of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and hydrogen cyanide – smelly gases with an odor similar to a horse stable.

Beyond Earth, each dome in this exhibition represents a distant, alien atmosphere, one that most humans can only imagine reaching, breathing in, and experiencing. While this may seem unattainable today, science has made incredible advancements in the past 50+ years. Who knows, maybe someday soon these dreamt experiences will become a reality.